If you are a teacher in Texas right now, you have likely experienced the “hallucination” phenomenon firsthand. You’re grading a well-written paper where the syntax is smooth and the vocabulary is elevated. But then you check the bibliography. The books don’t exist. The court cases are made up.

We are seeing this across the state not just because students are looking for shortcuts, but because they fundamentally misunderstand the tool they are holding. They are treating a probabilistic engine like a deterministic database. They are trusting a “ghost” that doesn’t exist (Bozkurt & Sharma, 2025).

To fix this, we need to strip away the sci-fi hype and define Generative AI with technical precision. As recent research from Sage, MIT, and the AFT confirms, we must define AI as:

“A probabilistic tool operating within a human-directed process.”

It sounds academic, but this specific framing is the key to restoring academic integrity. In plain language – Think of AI not as a “know-it-all” robot, but as a very advanced autocomplete that needs a human pilot to steer it and check its work. Here is how we use the latest research to turn the lights on in your classroom.

Part 1: The “Ghost” is a Prediction Engine

In their work The Ghost in the Machine (2025), researchers Bozkurt & Sharma warn us about the dangers of anthropomorphizing software—attributing human intent to code. When a student asks ChatGPT a question, the AI responds with a confident, human-like tone. But as Tom Chatfield notes in the Sage White Paper, we must not confuse “simulation” with “understanding.” An AI has “no stake in a conversation and no mind to change”.

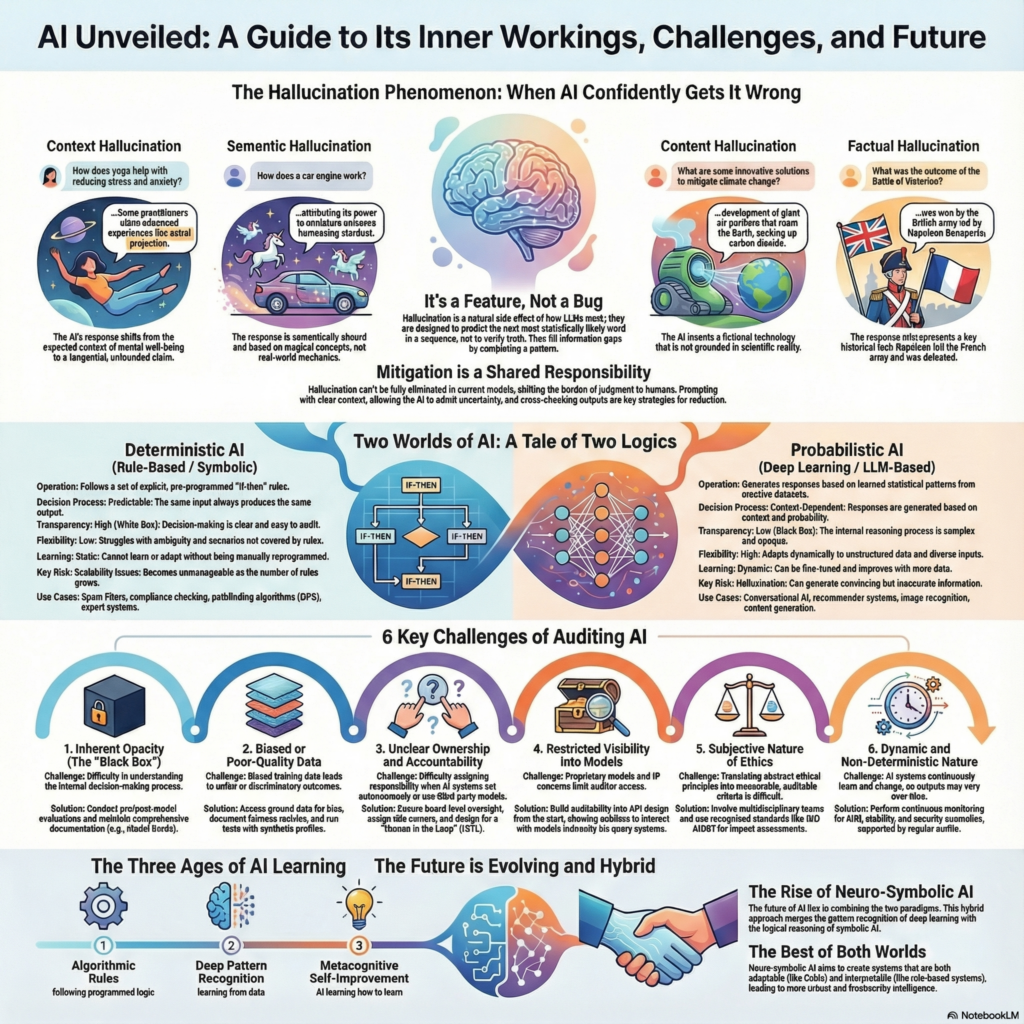

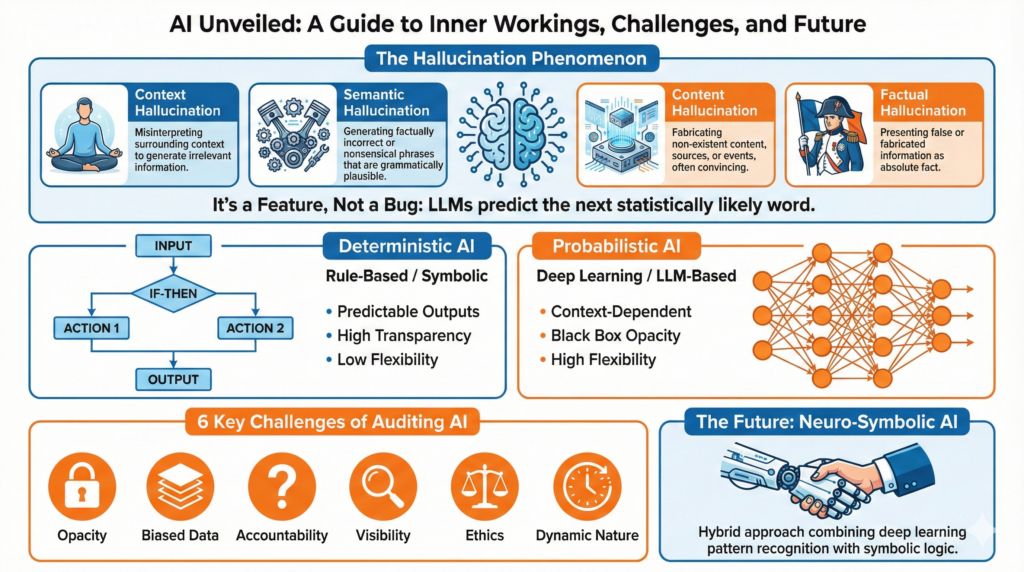

The Reality: The “Stochastic Parrot”

To understand why the AI makes up fake citations, we have to teach students that LLMs are “stochastic parrots”—they repeat plausible-sounding patterns without understanding truth. (Bender et al., 2021)

- Deterministic Tools (Search Engines): These retrieve existing documents. They deal in facts.

- Probabilistic Tools (AI): These are prediction engines. They calculate the statistical likelihood of which word comes next.

When an AI generates a fake citation like Smith (2021), it isn’t “lying.” It is simply predicting that “Smith” and “2021” are statistically probable tokens to appear in a bibliography. It prioritizes plausibility over factual correctness.

Part 2: Breaking the “Google Mindset”

The root cause of this crisis isn’t the technology; it’s the habits we ingrained over the last two decades. As the Guide to AI in Schools (2025) points out, students are applying a “Google Mindset” to AI: they type a query, skim the answer, and trust it.

This mindset is dangerous because, unlike a search engine, an AI does not retrieve information; it constructs it. When students operate “in the dark”—without understanding this distinction—they accept the AI’s output as truth rather than a probabilistic draft.

The “Oracle Fallacy”

We must teach students that AI is not an oracle. It is a “calculator for words” that requires constant verification. As the AFT’s Commonsense Guardrails (2025) emphasizes, students must be trained to “critically evaluate and use information… to identify and discount disinformation and misinformation”.

Part 3: The Solution is Human Direction

If the tool is probabilistic (and therefore prone to error), then the Human-Directed Process is the only safety net.

This framing counters the idea that “the AI wrote the paper.”

- The Reality: The AI is an instrument. It creates nothing without a prompt, a set of parameters, and a workflow designed by a human.

- The Implication: This preserves human agency. As the WISE/IIE report notes, we must ensure that “AI enhances rather than replaces human knowledge and capabilities”.

The PPP Framework: Prompt, Probe, Prove

To operationalize this, we replace the “Google Mindset” with the proposed PPP Framework which is a framework currently (2025) in development and testing by Kori Ashton.

1. PROMPT (The Setup)

The AI is only as good as the instructions it receives. Students must learn to frame the task, context, and constraints explicitly. As Chatfield argues, teaching prompt design is actually a lesson in “precision and clarity”.

2. PROBE (The Interrogation)

This is where we break the “passive consumer” habit. Students must question the output. They should ask the AI to explain its reasoning or offer a counter-argument. We must move from “ask once and accept” to “conversational, critical engagement”.

3. PROVE (The Verification)

This is the non-negotiable step for academic integrity. Because the tool is probabilistic, every claim must be verified.

- The Rule: If the AI generates a citation, the student must find the primary source.

- The Shift: We stop grading the final product and start grading the process. As suggested in the Guide to AI in Schools, we can ask students to submit “a slice of their conversation transcript” and “annotations explaining what they rejected, changed, or challenged”.

Part 4: Reframing Accountability

By adopting this definition—A probabilistic tool operating within a human-directed process—we fundamentally change the conversation.

We align with the AFT’s core value that technology must “promote human interaction” and never replace the teacher-student relationship. We align with the global perspective from WISE/IIE that graduates must be prepared to be “ethical consumers of AI content”.

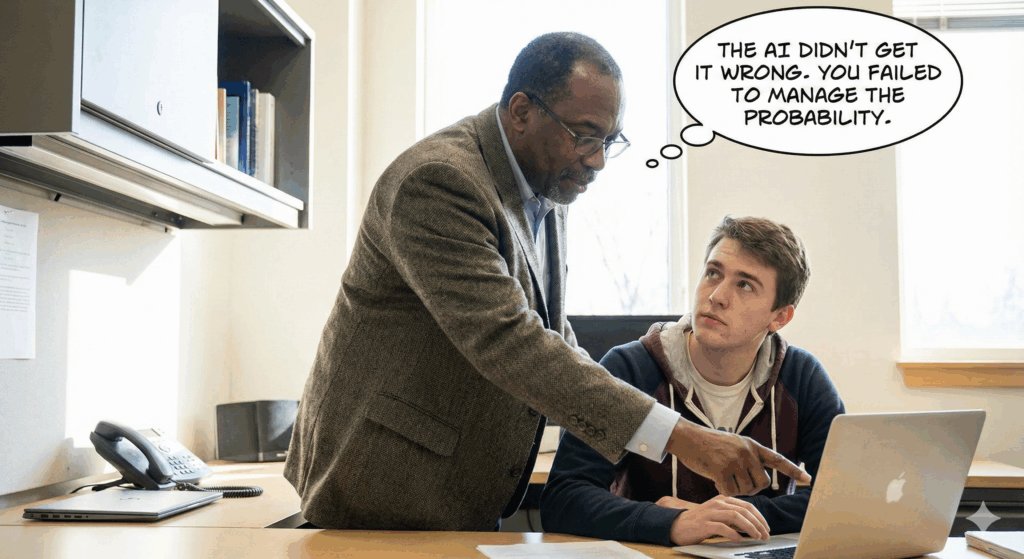

Most importantly, we put the responsibility back on the student. We tell them: The AI didn’t get it wrong. You failed to manage the probability.

Let’s turn the lights on. Let’s stop grading the ghost.

References

American Federation of Teachers. (2025, March). Commonsense guardrails for using advanced technology in schools.

Ashton, K. (2025, November 26). From the “Google mindset” to AI literacy. Texans for AI.

Bender, E. M., Gebru, T., McMillan-Major, A., & Shmitchell, S. (2021). On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big? 🦜. Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 610–623. https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922

Bozkurt, A., & Sharma, R. C. (2025). The ghost in the machine: Navigating generative AI, soft power, and the specter of “new nukes” in education. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 20(1).

Chatfield, T. (2025). AI and the future of pedagogy (White Paper). Sage.

Martel, M., Talha-Jebril, S., & Beriashvili, S. (2025, November). Navigating skills adaptation: Integrating AI in higher education. Global Consortium on AI and Higher Education for Workforce Development. WISE & IIE.

Smith, J. M., Dukes, J., Sheldon, J., Nnamani, M. N., Esteves, N., & Reich, J. (2025, August). A guide to AI in schools: Perspectives for the perplexed. Teaching Systems Lab, MIT.